(L-R) Joel Embiid, Michael Rubin, Meek Mill and his son Papi pose after Philadelphia's playoff win against Miami (Photo by Drew Hallowell/Getty Images)

At some point, a light bulb turned on in Rubin's head. He knew the system was not working for Meek, but the more he saw, the more he began to comprehend that Meek's story was not unique; it was a part of a bigger narrative. "What started as a sole focus to save my boy turned into a much bigger mission as I learned about a completely broken criminal justice system," he said, adding: "Meek always used to tell me, 'Michael, there's two Americas—there's America and then there's black America.' I didn't believe him and I kept telling him there's one America. After going through this experience with Meek, I can tell you he was right and I was clearly wrong. This situation opened my eyes because I would've never understood the criminal justice system's unfair treatment of young black men."

Meek told me that he, too, sensed the change in Rubin. "It's like this, it's real simple—he's a white Jewish billionaire guy and he became friends with a black kid from the ghetto that actually rose up above all that and started doing his own thing. But then when it all happened, he'd never witnessed this side of the system ever in his life, because he was never treated this way," Meek said. "For him, he's like, 'How did my friend just get a four-year sentence for not committing a crime?' For him, it's like, 'I've never seen no shit like this, and it doesn't sit well with me.'"

Rubin figured Meek could use more people—people in positions like him, people of affluence or power, people who needed their eyes opened—in his corner, so he brought more influential friends with him on his trips to Chester. In April, he invited Patriots owner Robert Kraft to tag along and when they got to the prison, Kraft was deeply moved by what he saw.

“I remember Robert was shocked by how well Meek was keeping it all together," Rubin said. "Robert asked him how he managed to stay strong, and Meek said, 'This has been my whole life. It's all I know, but for the first time, I have people fighting for me. And I'm so appreciative of that.' That really stuck with Robert."

A few weeks later, Rubin brought actor-comedian Kevin Hart, another Philly native, to visit Meek. Then an odd thing happened, something completely unexpected: The Pennsylvania Supreme Court ordered Meek's release. The sports and entertainment world rejoiced. Cue the chopper. Cue the Dreams and Nightmares.

—

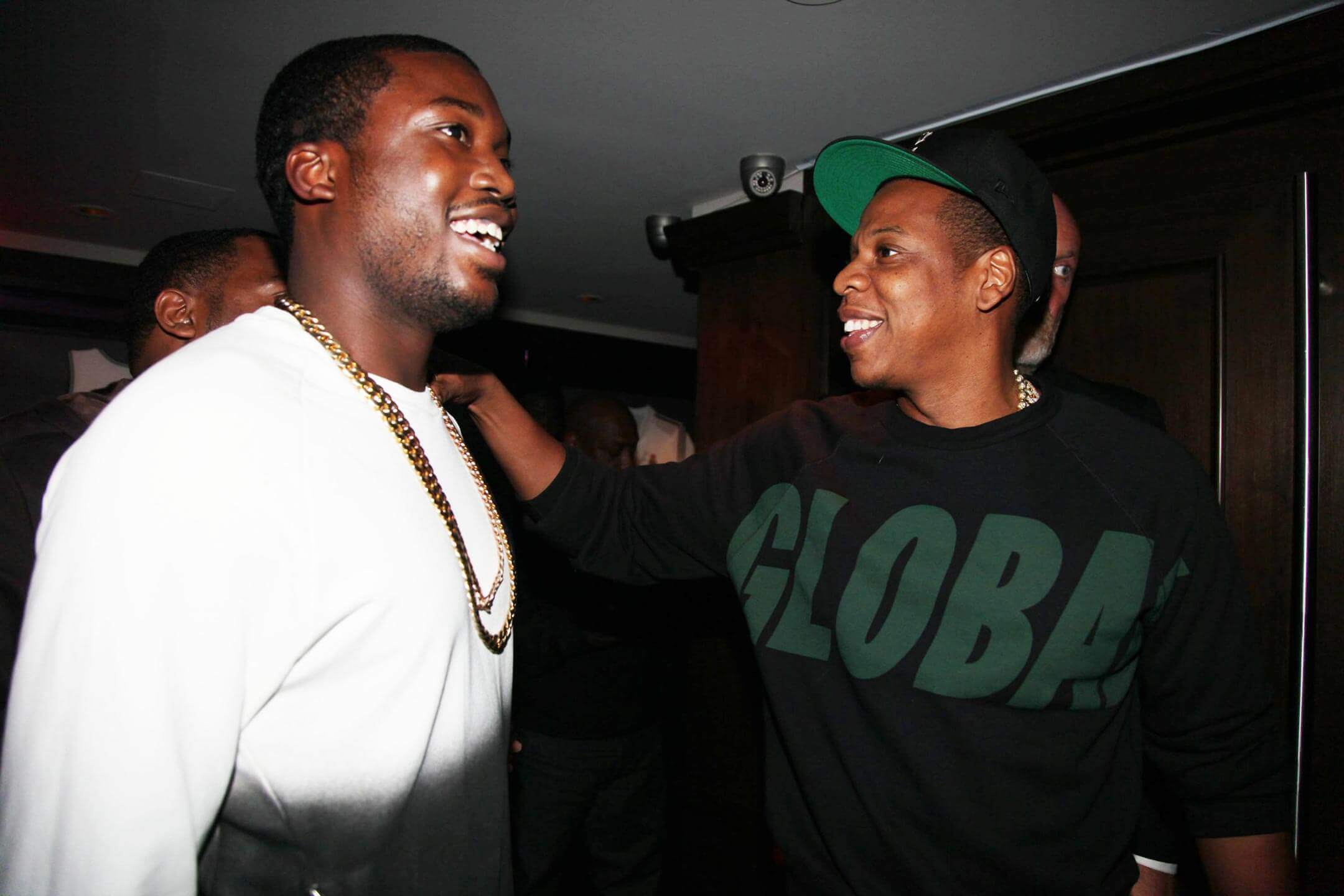

On June 8, Meek threw a thank-you dinner at the overwhelmingly extra restaurant TAO Downtown, in Manhattan. Inside, gallery-esque statues and light fixtures filled up the room. More than 40 people—the sheer number of invitees at this dinner made you realize how large of a team was involved in getting Meek out of jail—gathered near a table set up in the back of the cavernous room that extended the width of the restaurant. There were members of his legal team, reps from Roc Nation and high-profile supporters like Carmen Perez, the executive director of The Gathering for Justice, a nonprofit focused on the racial inequities in mass incarceration. (Rubin was noticeably absent.) It was an ideal setting to be distantly seen, but not overheard.

When Meek showed up, the energy in the room shifted. Everyone paused their side conversations and was either waiting to talk to him or waiting to be introduced. It was an odd sight to behold, initially; a young black man in a sea of powerful—mostly white—people with their hands outstretched. I found myself resisting the easy urge to go straight down the cynical route, one in which I wondered whether Meek should fully trust their goodwill. (What would their favors cost him down the road?) But I also got the sense that those around Meek truly believed he didn't do anything wrong—something Meek confirmed with me later.

"If I committed a crime and I got locked up, Mike Rubin wouldn't be there. Roc Nation wouldn't be there. Nobody would be there because it's my mistake," Meek said. "They'd be like, 'You went out and made a choice and did some fuck shit that you didn't have no business doing.' Wheelieing a bike? I been wheelieing a bike since I was fucking 13 years old and never been to prison for it not one time."

As the dinner progressed, Meek made his way around the table, spending time with each attendee. “I’ve been through a lot of stuff where we didn’t have this type of support. Where we didn’t haven’t anybody really caring about us like that except for our mothers and our immediate family,” Meek would say later. “So to have this type of support, it’s a good feeling.”

The past six months had clearly taught him a great deal about himself, what he can handle and the type of person he's trying to allow to bubble to the surface. So much of his life, perhaps unfairly, is based on people's perceptions of him, based on what they've heard or what they assume. And he knows those perceptions come down to how he behaves when he's front and center.

So it had to be a wheelie, right?

It was two days after the dinner, at New York radio station Hot 97's annual Summer Jam concert at MetLife Stadium in New Jersey—Meek's first scheduled performance since being released on bail. He sat backstage on an ATV, awaiting his moment. When it was time for his set, Meek drove out in front of an electric crowd, revving the engine. "Ain't this what they been waiting for?" The music blasted in the background. Meek, dressed in motocross gear and a gold chain, popped up on the rear two tires—a move that had the entire crowd buzzing—before landing, grabbing a mic and addressing the crowd. "I used to pray for times like this, to rhyme like this," he rapped.

Was it a brash middle finger to a system that he continues to play tug-of-war with? Or was this another act of irresponsibility—a sign that Meek doesn't deserve to be free?

For Meek, the move was a clear refusal to deny aspects of the environment that made him who he is.

"I'm a rapper from 18th and Bridge, North Philadelphia, so to be in a stadium with that many people cheering for you, when you doing something positive, it's one of the biggest blessings," he said. "It was another day at the dream for me. It felt good when I left the stage—shit like that boosts your self-esteem as a person, makes you value yourself more, makes you more confident. ... And because people see me go through trials and shit and still be able to stand tall and hold my chin up high, they buy into me a little bit."

**

On the morning of June 18,

"I've had two babies and Meek Mill still in court," a man from One Day At A Time, a community-based recovery organization, barked to a round of applause. A few minutes later, the West Powelton Drummers, a well-regarded local drumline that has become a staple at 76ers home games since 2014, arrived. They wore 76ers shirts with "Free Meek" on the back. Following their processional, CNN commentator and Temple University professor Marc Lamont Hill took the lectern. "The system is not broken," he said authoritatively. "The system is doing exactly what it was designed to do, which is put poor people in jail."

When Meek showed, he was clad in "Free Meek" paraphernalia of his own—a hoodie—much to the crowd's delight. With about 10 minutes left before his scheduled hearing, he walked on stage to address his supporters. No notes, no teleprompter, fully off the cuff.

"I spent Father's Day with my son last night. And if it weren't for people like y'all, I wouldn't have been able to be here today, so thank y'all," Meek said, to a chorus of cheers. "You know, there's people that's locked behind the walls, caught up in the darkness, who don't have the support. So I hope that we get people behind them like myself. And we stand up for people that's caught up in the system that don't belong there."

After his speech, Meek walked upstairs into the courthouse, followed by a throng of folks hoping to sit in on the proceedings. The scene inside was madness; guests were required to lock up their cellphones. Meanwhile, outside Room 908, Meek checked in with members of his family and stole a few extra moments sitting with his seven-year-old son, Papi. He had the controlled nervousness of someone in the waiting room for an interview and the eagerness of a man ready to take his final test. After one final bathroom break, he and his team of lawyers disappeared inside the courthouse room. The crowd was told to wait outside. The whole process was nerve-racking.

Many on Meek's team assumed the hearing would be a short affair: The defense had no witnesses to call, and the Philadelphia district attorney's office supported a new trial. But the proceedings lasted over two hours. In one respect, this was to be expected: Meek's experience with the unfairness of the justice system stems from a series of interactions he has had with Judge Brinkley in the past. The hearing was just the latest confrontation.

In another way, the lengthy day in court was inevitable. Both sides have reached somewhat of an impasse when it comes to Meek's standing: Judge Brinkley considers Meek "a danger to the community," whereas Meek sees himself as not a threat at all. It's an incredibly layered conundrum—one that, listening to Meek tell it, is as much about criminal justice as it is about race as a function of class.

"You think the Eagles organization would be coming out to my songs if I was a threat to Philadelphia?" he would ask me days after the hearing, impassioned. "You think the owner of the Sixers would be standing behind me if I was a threat to the Philadelphia community? The governor wouldn't be standing anywhere near me if he thought I was a threat to the community. But you got a black lady in the courtroom saying I'm a threat. What it seems like we're really talking about is labeling young black people that come from poverty as a threats to the community." —

After two hours, Judge Brinkley decided she didn't have enough information to determine if new evidence presented by Meek's legal team warranted a new trial in his decade-old conviction. When the news made it out to the crowd outside the courthouse, some smiled because she declared the evidentiary hearing a no-decision. Others showed their frustration, claiming the hearing was a complete waste of time. "A circus," many called it as they exited the courtroom.

Word soon spread that Meek was coming down. In the building lobby, members of the family and his inner circle stood, hugging and shaking hands. When Meek emerged from the courthouse elevator, he had shed his "Free Meek" sweatshirt for an orange shirt with photo of an old mugshot. It was an image of 18-year-old Meek, sporting braids and a bandage over his right eye—the cover art from his 2016 mixtape DC4.

Papi was under Meek's arm, and a team of lawyers walked alongside them. After passing through some revolving doors, Meek was met by a sea of reporters and onlookers, with microphones and cellphones extended, hoping to document every moment. One of Meek's lawyers made a statement, and then Meek picked up Papi and handed him off to a family member before taking the stage.

Meek thanked everyone for the continued support, but not before expressing his frustration. "I feel like what went on in the courtroom today is disgraceful," he said at the lectern. (One of Meek’s lawyers said that he observed Judge Brinkley laughing during testimony from an expert witness.) "There was laughing going on, and to me, it's not really a game."

He was then whisked away to go take care of who knows. "At least he came out, because he didn't have to do that," said a woman, who was filming on her flip phone.

**

This was his life now. And it wasn't a movie, because you couldn't invent his story if you tried.

Luckily for Meek, he seems uniquely built for what's ahead. He's not worried about the negative chatter. "I come from the hood," he told me. "Where I'm from, if your mom on crack, they going to bust on your mom. If you got fucked-up sneaks or clothes or you don't have a place to live, people will fucking torment you and rip your self-esteem apart, seven days a week. So when the internet come with random people just talking shit, for people that come from where I come from—we can handle it."

He's already turning his story—and what's been on his mind as of late—into music. ("They were screamin' 'Free Meek!'/ Now Meek free, judge tryna hold me," he raps on "Millidelphia.") He's trying to carve out time to decompress, to maintain himself the best way he knows. "I'm just always trying to adjust and adapt, switching gears," he told me. "Just trying not to overheat, you know what I'm saying?"

Philly's current superstars are optimistic about what is to come. "I know he came out of this situation stronger than ever and he'll continue to have a positive impact on the Philadelphia community and, really, the entire world," Embiid said. "I look forward to supporting him any way I can." The city's native sons continue to show Meek love. "I've known him since we were kids playing at the same gym," Raptors point guard Kyle Lowry said. "He's a proud man and the things he's been through has only made him tougher and more impactful on the world. And he worked hard to get to the point where he can be able to use his talents to help give back to our community and our city."

Power is influence. There is no indicator of power quite like the ability to change people's minds and actions. Meek has changed a lot of minds. He's not changed others. But there is also power in enduring in the face of those changes. What Meek has proved is that he's a survivor. It's that perseverance that has forced people to care.

Meek, himself, is clear about his aims: He wants to make an invisible population increasingly more seen.

"I had to go to jail for six months to earn people's respect," Meek said. "But, I think right now, my word is more powerful because I was given a platform and have all this light on my situation, and people actually know I've been through some real shit. But if you ask me what I've always been about, I represent the struggle, the streets and the poverty of where I come from.”